By Nicklas Balboa and Richard D. Glaser, Ph.D.

Published in: Psychology Today

How love, consciousness and imagination play key roles in our evolution.

“Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world.” - Albert Einstein

Why are humans such keen storytellers? It is because our frontal, parietal and temporal lobes contain areas that are specialized for complex language production, processing, and comprehension. The neocortex is the home of complex thought that gives us the power to imagine, create, and communicate with others. While the true origin of our cortical expansion is heavily debated, our neocortex increased in size possibly due to the advent of tools which allowed for changes in diet. For example the invention of the spear allowed us to hunt larger game, providing access to rich meats, or the discovery of fire, which allowed us to cook food.

The abilities of the neocortex to create new brain cells, or neurogenesis, along with pressures for greater co-operation and competition with our early ancestors are also strong candidates for the expansion of association areas of the brain. (Hoffman 2014 & Dunbar 2007)

Ultimately these factors contributed to an increase in the size and functional connectivity of the neocortex. This increase in size has led to greater voluntary control of social behaviors, and one day hopefully may lead to social harmony.

Evolution of the Brain

Over the last several million years the human brain has nearly tripled in size (Hawks 2013 & Kaas 2006). Professor John Hawks, an anthropologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, claims that the Australopithecine brain began to show subtle structural changes in the neocortex, which began to expand and reorganize function. 1.9 million years ago Homo habilis saw the expansion of language dependent areas of the frontal lobe such as Broca’s Area (Hawks 2013). The most recent growth spurt our brains went through, and largest in terms of volume, saw the creation of the modern neocortex and its vast array of complex cognitive functions (Hawks 2013 & Kaas 2006).

One of the most advanced cognitive functions we have is our ability to create, understand and share language. Words, despite their objective Webster definitions, have unique meanings to those that perceive them. As my mentor, Judith E. Glaser used to say, “Words create Worlds.”

Something Greater than All

One word that certainly seems to create our world is love, a word that is far reaching and far misunderstood. In practice, love is not a word people ought to use to gain conversational ground by leveraging information or "facts" whether they be of faith or science, to assert dominance over another's stance. When we focus on dynamics such as “asking and telling” we create platforms for the exchange of information that we already know, often seeking to validate our point of view. This is a Level 1, or transactional conversation (Glaser 2016). Rather, love is a symbol for something greater than us at every scale, a benchmark for true understanding and the creation of WE, as opposed to the creation of I.

Semantically, love represents the point of no return; the discovery of a symbol of complexity and awe that adds a mystic touch to our origin story as humans. We believe that love is a part of us, that love is the creator, and the protector of all existing things. While atomic energies of entropy aspire to disarray, our human concept of love binds our perceptions together into a fluid life experience. With our love we maintain a relationship of pure faith, just as our conscious mind does with our bodies.

A Transition to New Thought

Over the course of hominid history it was our brains that developed the ability to navigate the world. Navigation is a cognitive process that requires the ability to plan routes using maps; it means visualizing different routes in our minds and planning how to get there. It is a reflection of our cognitive, conscious abilities to create mental maps of ourselves, others, and the natural world around us. Surely without this incredible, imaginative competency we would never have transgressed natural order into the modern age of agency and volition.

When making decisions our senses provide information that is cognitively represented as schemas or ‘maps’, in the form of bio-electrical input, that serve as benchmarks for desired, familiar, and even learned results/situations/experiences.

For example, suppose you are given a choice of three different dishes for dinner. When they are revealed your brain will engage in a complex and almost informationally infinite dance with the three foods, producing sights, smells, sounds, textures and tastes into a convenient experience that we humans call consciousness.

When choosing a meal these schemas will prepare the conscious mind, if you can resist the urge to eat with your heart, with values that are pertinent to the organisms’ current needs. It could be that you need to eat choice 1) salad because you are malnourished, and your body’s nutritional needs are pushing that information to the cognitive bin. It could be that you need to eat choice 2) pizza because your mood is low, and nostalgia serves as an elevator. It could be that you need to eat choice 3) both because you are Homer Simpson.

When making these complex decisions we need a way to navigate the infinite amount of information that is given to us in short meaningful chunks. Ring the bell for dinner and it is our drives that answer. Ask someone what they want, and the conscious mind begins to reach out to salient schemas, allowing the individual to weigh options by visualizing routes and ultimately choosing what food they want.

The conscious mind gains experience through processes like learning and memory, deciding which schemas are useful and which are not. This endogenous feedback system is similar to the interpersonal relationships we maintain in that they require feedback from others, and within that fact lies the ultimate truth of the subjective human conscious experience. Self-consciousness requires others to exist.

Synchronized States

Not only do our brains utilize areas of the neocortex for communication, they also synchronize with each other. A study from Princeton University, using fMRI to record brain activity from both speakers and listeners during natural verbal communication, shows how a speaker’s brain activity is coupled with the listener’s during successful communication (Stephens 2010). This coupling of brains, or synchrony, disappears when we fail to communicate. As an example, when speakers communicate with a listener who does not understand the language of the speaker, they fail to synch.

Perhaps in the search for individual consciousness, we are missing out on a defining feature of its existence. It is not absurd to think that awareness ought to increase when signals synchronize across groups. This is exactly how prosocial movements integrate into the status norm, by gaining traction (usually through an affect image) via spread awareness. When we interact with a similar frequency with one another, consciousness functions more like music; when two or more similar notes, vibrations, or frequencies play simultaneously, both inputs resonate and create an amplification of the signal. This external synchronization of awareness is also reflected by the internal activities of the brain.

There is ample empirical evidence, from Hans Berger to Christoff Koch, of the various wave states that the brain instantiates, from low state delta waves to normative beta waves to high frequency gamma waves (Riedner 2008). Brain waves change in accordance to our current state (i.e. intensity of moods, thoughts, waking versus dreaming). These waves are the result of synchronized electrical communication within single neurons and between groups of neurons. At large scales, these symphonies of mental activity coalesce into certain frequencies that are consciously experienced due to their ability to organize neural information.

For example, how does the brain make a mental model of a tree? The brain uses words to create mental concepts, like “Tree". A “Tree” can have certain characteristics and do certain things:

Source: Open Clipart / Pixabay |

Is | Does |

| Green | Grow | |

| Tall | Fall | |

| Alive | Make noise |

In order to easily and efficiently communicate what a tree is, we humans created the concept to describe the variety of instances that can encompass a “Tree”. In objective reality, green and noise do not exist. They are brought into our perceptions by our sense organs and organized by our brains. When visually processing a tree, your brain detects the different branches, leaves, and colors that make up the sapling, however you experience the tree as a singular, unified object. In theory, just as external signals synchronize and resonate, so do internal signals.

The different neurons encoding color (i.e. brown and green) and the different neurons encoding objects (i.e. branches, trunk, and leaves) need to synchronize and integrate in order to construct a unified tree. As these neurons fire, they form an ensemble that resonates in activity. This is based on Hebbian Theory, which states that cells activated at the same time tend to become associated. Overtime the synapses strengthen and grow in number, allowing for their activity to facilitate one another's (Hebb 1964).

Therefore a “Tree” is an experience constructed when the world and a detecting body interact. The concept only becomes meaningful in the viewer’s mind, and the minds of all others who agree with the concept “Tree”.

In this sense we can view self-consciousness as the ability to functionally organize mental activity into certain frequencies, or oscillations. These frequencies ultimately coalesce into an 'experience' or ‘story’ for the perceiver across space and time, in an egocentric domain. Without external input, and the ability to internalize, associate, and learn from this information, the conscious mind would lie dormant in a vat of fatty tissue and fluid, similar to Descartes’ thought experiment.

Upon reviewing his concerns of dualism, a key word appears, ‘I’. “I think therefore I am.” However the word ‘I’ refers to a distinction of self and the notion that there is a group (WE), and that ‘I’ am a distinct property or instance of this group (WE). One could conclude that this recursive sense of self necessitates the ability to distinguish one’s self from a set of others, therefore the ability to become aware of the self stems from knowledge of others existence.

Although counterintuitive, this model provides an explanation for what it is really like to be conscious. This superimposed state constitutes the the awareness of both the I (internal self/egocentric) and the WE (objects and other subjects/allocentric).

Tying the Knot

The preservation of a culture is dependent on humanity’s unique mastery of language, which allows us to transmit customs and beliefs across generations. We share these beliefs through the art of storytelling: combining words to construct narratives that create greater meaning through social context and learning. This means that we humans are constructors of our own unique realities, and as a resulting subset, culture.

As humans began to form societies and cultures their awareness of one another amplified in intensity. This enhanced consciousness accounts for the need of a set of rules, or morals, that integrate all members of the group in such a fashion that benefits the fitness of the entire group. No weak links. But what could serve as the ultimate rule, something that could quell all instinct in a moment of heat and promote social harmony? Well, do you remember love?

The idea of love encapsulates something so powerful that it marries the very nature of the soul and the body. We as a community are a part of something that is much greater than the individual, and we as an ecology are a part of something much greater than human beings. Within the vast infinities of the human mind we came up with the idea of love, and it is a natural reflection of the world around us.

It’s been a long time since the inception of love into human society, and sometimes we get caught up in this fast life and forget that our origins belong to the story of love.

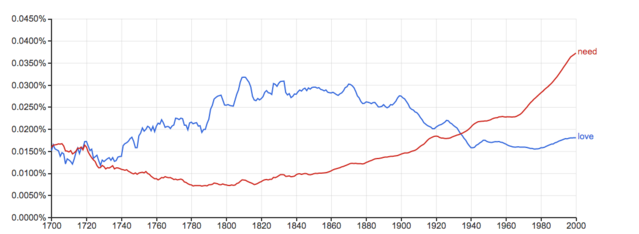

The American English corpus is a collection of over 560 million words. you can search this database via Google ngram and the program will return a graph showing the frequency of the searched word’s usage in published literature across time. At one point in time in the English language, love was the driver. Over time the needs of the individual overcame the unity of a shared reality and ushered in the age of the individual and their needs.

We now live in a culture that is hyper aware of itself and its decisions. With this enhanced awareness comes expectations, which can create prolonged mental states such as anxiety. However the beauty of consciousness is as we are aware of this, we can discover a way to reappraise the context of the situation so that it becomes beneficial to us.

We humans are the perceivers, the judgers and most of all the lovers of all that we see and experience. We imagine, perceive, and act upon the world that we create in our mind’s eye. Perhaps our most imaginative creation is the idea of love. It gives us a sense of connection and warmth that adds profound purpose to our story of life. Without love, life is merely a series of decisions to be or not to be.

References

Hawks, J. (2013). How Has the Human Brain Evolved? Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-has-human-brain-evolved/

Kaas, J (2006). Evolution of the Neocortex. Cell Press, Retrieved from https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(06)02290-1.pdf

Dunbar, R. I., & Shultz, S. (2007, April 29). Understanding primate brain evolution. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2346523/

Glaser, J. E. (2016). Conversational Intelligence: How Great Leaders Build Trust and Get Extraordinary Results. Routledge.

Balduzzi, D., Riedner, B. A., & Tononi, G. (2008, October 14). A BOLD window into brain waves. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/105/41/15641

Hebb, D. O. (1964). The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. New York: John Wiley.